Here's the next installment in a series of posts intended to answer partwriting questions. In this post, I'll discuss some basic rules of harmonic progression.

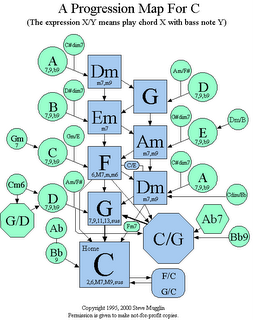

"How do I know what chord follows another chord?" Very often, the answer is revealed to you in a diagram that looks something like this:

(image from Richhoncho chordmaps)

Simple, no?* Here is, I think, a much simpler way of figuring out what chord should come next.

Chords basically function in three different ways. Chords can be tonic-functioning (we'll abbreviate these chords with a T); they can be dominant-functioning (we'll abbreviate these with a D); or they can be predominant-functioning (we'll abbreviate these with a P).

Tonic-functioning chords are stable. They begin and end phrases, movements, and entire pieces of music. They don't need to resolve; they don't feel like they have to go anywhere.

Dominant-functioning chords are active, unstable, and require resolution. They are what drives music forward. Dominant-functioning chords need to resolve to tonic-functioning chords.

Predominant-functioning chords are somewhat less unstable than dominant-functioning chords but they tend to want to move to dominant-functioning chords. Occasionally, one will move to a tonic-functioning chord.

Here's how to classify the chords you (hopefully) already know into these three big categories:

The classification above includes seventh chords with the same roman numerals and takes into account root position and first inversion for triads. Second-inversion triads need special treatment: that' s a topic for another post. All inversions of seventh chords should work in this model.

Now, throw away your chart. Here's all you need to know. To create an effective harmonic progression in the common practice style, you can string together the letters T, P, and D in any order provided that a P never follows a D. All of these will make coherent harmonic progressions:

T-P-D-T (could be realized as I-ii-V-I)

T-T-P-D-T (could be realized as I-I6-IV-V-vi)

T-T-T-T-T-T (could be realized as I-I6-I-vi-vi6-I)

T-D-D-T (could be realized as I-vii-V-I)

...and so on. Once you come up with a string of Ts, Ps, and Ds, simply substitute a chord with the corresponding function into your string. Then all you need to do is follow the rules of partwriting and you should be well on your way to successful theory homework.

*Note that this chart only works for C major. If you want to write a piece in a different key, you need a new chart. I suspect minor is even more convoluted.

**Secondary dominants present an interesting case. On one level, you have a dominant-functioning chord resolving to a tonic-functioning chord. On another level, the secondary dominant (say, V/V) is operating in some other way--in this case, as a predominant-function moving to a dominant-function.

"How do I know what chord follows another chord?" Very often, the answer is revealed to you in a diagram that looks something like this:

(image from Richhoncho chordmaps)

Simple, no?* Here is, I think, a much simpler way of figuring out what chord should come next.

Chords basically function in three different ways. Chords can be tonic-functioning (we'll abbreviate these chords with a T); they can be dominant-functioning (we'll abbreviate these with a D); or they can be predominant-functioning (we'll abbreviate these with a P).

Tonic-functioning chords are stable. They begin and end phrases, movements, and entire pieces of music. They don't need to resolve; they don't feel like they have to go anywhere.

Dominant-functioning chords are active, unstable, and require resolution. They are what drives music forward. Dominant-functioning chords need to resolve to tonic-functioning chords.

Predominant-functioning chords are somewhat less unstable than dominant-functioning chords but they tend to want to move to dominant-functioning chords. Occasionally, one will move to a tonic-functioning chord.

Here's how to classify the chords you (hopefully) already know into these three big categories:

Tonic-functioning chords: I, vi, and sometimes iii; in minor, i, VI, and sometimes III. (Tonic-functioning chords rely on scale degrees 1 and 3 for their identity).

Dominant-functioning chords: V, vii, and occasionally iii (in major). (Dominant-functioning chords rely on scale degrees 5, 7, and 4--the tendency tones--for their identity).

Predominant-functioning chords: ii, IV, and everything else not listed above (including augmented sixths, Neapolitans, and secondary dominants**) (Predominant-functioning chords rely on scale degrees 2 and 4 for their identities; altered forms of these scale degrees exhibit the same functionality.)

The classification above includes seventh chords with the same roman numerals and takes into account root position and first inversion for triads. Second-inversion triads need special treatment: that' s a topic for another post. All inversions of seventh chords should work in this model.

Now, throw away your chart. Here's all you need to know. To create an effective harmonic progression in the common practice style, you can string together the letters T, P, and D in any order provided that a P never follows a D. All of these will make coherent harmonic progressions:

T-P-D-T (could be realized as I-ii-V-I)

T-T-P-D-T (could be realized as I-I6-IV-V-vi)

T-T-T-T-T-T (could be realized as I-I6-I-vi-vi6-I)

T-D-D-T (could be realized as I-vii-V-I)

...and so on. Once you come up with a string of Ts, Ps, and Ds, simply substitute a chord with the corresponding function into your string. Then all you need to do is follow the rules of partwriting and you should be well on your way to successful theory homework.

*Note that this chart only works for C major. If you want to write a piece in a different key, you need a new chart. I suspect minor is even more convoluted.

**Secondary dominants present an interesting case. On one level, you have a dominant-functioning chord resolving to a tonic-functioning chord. On another level, the secondary dominant (say, V/V) is operating in some other way--in this case, as a predominant-function moving to a dominant-function.