This is the text of a talk that I gave at a conference that the Seattle Symphony hosted in March 2014. More to come…

In an interview with Vera Lukomsky, Sofia Gubaidulina scolds people like me: “Musicologists do not know how to describe my style and just attach inaccurate labels to my music! I think this is theoretical piracy! And I protest against the label ‘eclectic,’ which musicologists pin on Bach. Of course, he used plenty of borrowed material (from Buxtehude, Vivaldi, Corelli, and many others), but Bach did not care about style at all. He thinks about God, he talks with God in his music!” (Lukomsky 27). Against the backdrop of this caveat analyst, if I may, I’m going to do my best to avoid “theoretical piracy” as I talk about Gubaidulina’s musical borrowing from Western composers. I’ve limited the talk to borrowing from Western composers because it seems in line with the theme of this weekend’s conference. Gubaidulina borrowed from a wide variety of sources: her works feature elements of popular music, jazz, Western art music, and Central and East Asian music as well.

In this paper I’m going to look at what she borrows, how she borrows it, and why she borrows. Robert Hatten’s distinction between strategic and stylistic intertextuality illuminates what she borrows, and Peter Burkholder’s typology of musical borrowing explains how she borrows. Why she borrows is a more complicated question. I contend that Gubaidulina’s borrowings represent not only an effort to connect with composers and music from other eras, but also a method of manipulating the listener’s experience of time. I’m going to start with Sieben Worte, follow with the piano sonata, and conclude with Offertorium.

Sieben Worte

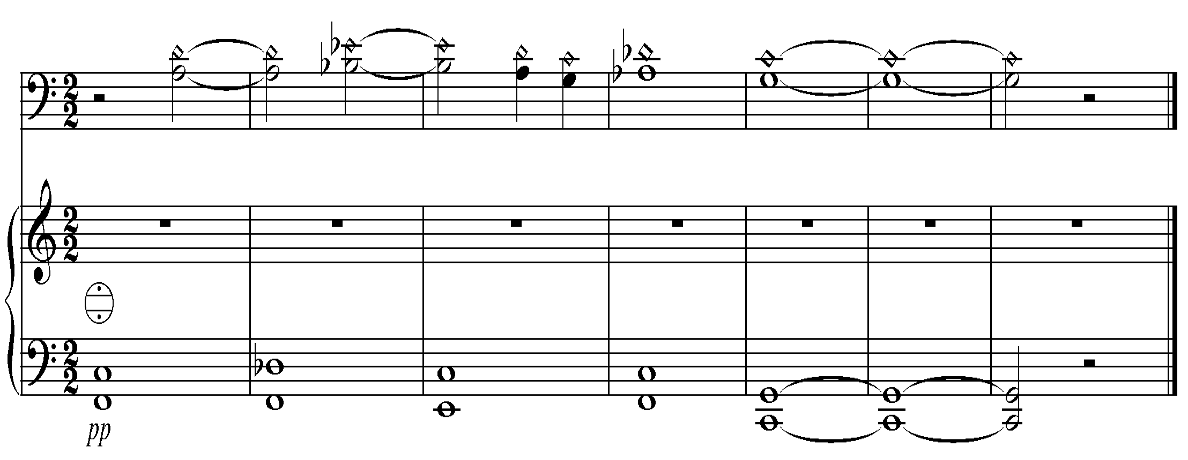

Sieben Worte was composed in 1982 at the suggestion of Gubaidulina’s cellist friend, Vladimir Tonkha. Following his performance of Haydn’s Seven last words, he remarked to Gubaidulina, “Both Schütz and Haydn have written Seven words; why don’t you do it, too?” (Kurtz 166). The composition is for cello, bayan, and string orchestra, and it’s in six movements. The cello is associated with Christ on the cross, the bayan with God, and the string orchestra represents the holy spirit, the Evangelist in Schütz’s work. Gubaidulina includes a direct quotation from Schütz’s Seven words; namely, his musical setting of the words “I thirst.” Schütz’s setting, which dates from 1645, can be found in Example 1.

The passage is noteworthy because of the dissonances that result from the metric displacement of the voice: the resulting augmented and diminished intervals make the passage stand out. The unexpected resolution to the minor—a sort of cross relation—at the end of the gesture (the boxed notes in Example 1) adds to the strangeness of the passage. It is this tag at the end that provides Gubaidulina with much of the melodic material for the work. I describe this figure as a “sort of cross relation” because it yields Gubaidulina’s symbolic gesture of “crucifying” the string. Example 2 contains the first measure of Sieben Worte, featuring the “crucifixion” (you can read more about this in my Music Theory Online article).

From a symbolic standpoint, something very interesting happens here, I think. The motive has associations in the musical, textual, and gestural worlds. On the one hand—independent of any other information—the cross relation makes the passage strange. On the other, a listener familiar with Schütz’s work will associate the passage in Sieben Worte with the text “I thirst.” The “crucifixion” gesture also conveys a strong physical symbolism to those familiar with Gubaidulina’s musical language. Thus this little chromatic gesture is laden with many potential meanings.

This melodic germ—the boxed notes in Example 1—provides Gubaidulina with much of the work’s melodic material: this is the first way in which she borrows from Schütz. The material serves as a motive throughout and is transformed in a variety of ways, shared among the cello, bayan, and string orchestra. There are more direct references to Schütz’s setting over the course of the piece. The first movement begins with interplay between the solo cello and bayan, both largely circling around the A below middle C: the “crucifying the string” that I discussed earlier. The first instance of the full quotation, which can be found in Example 3 appears after this opening, but before the string orchestra enters.

Following a symbolic cross drawn in the score and performed by the soloists, the cello—the voice of Christ on the cross—intones the “I thirst” motto in ethereal artificial harmonics and the bayan provides the harmonic foundation. This quotation functions as the understated climax of the movement: it calls attention to itself by virtue of its rather traditional harmony and texture, which stand in sharp contrast to the extended techniques showcased in the preceding music. In this sense, the passage is marked in the same way Schütz’s setting is: it stands out from the surrounding material as a result of its chromatic nonconformity. The quotation also calls to mind—for those who recognize the source—the text that Schütz set. Another instance of the quotation appears (coincidentally) at rehearsal 10 in the third movement. In this instance, the bayan has the melody and the cello provides harmonic support, and the final full quotation occurs (not surprisingly) at the end of the fifth movement, “Mich dürstet.”

This borrowing is an example of what Hatten calls strategic intertextuality: Gubaidulina quotes a specific passage from a specific composer. The quotation functions in two ways: it provides the motivic material that shapes much of the composition, and it appears as a (more or less) direct quotation, typically at climactic moments. Why she borrows is a more complicated question. Gubaidulina tells Vera Lukomsky that she uses musical quotations as epigraphs: “A writer wants to adjoin, to come into contact with, a person who lived a long time ago. And the epigraph is a point of meeting or contact with another writer” (Lukomsky 1999, 26). She rejects the term “polystylism” as a description of her work, arguing that her use of quotations differs from Schnittke’s. Nonetheless, I would contend that it’s not what she quotes or how she quotes it, but the seams that emerge from the practice of quotation that are of interest here.

The French literary critic Gerard Genette includes a chapter on epigraphs in his book on paratexts. Generally speaking, paratexts are ancillary materials that shape the way a core text is interpreted: things like titles, dedications, pseudonyms, interviews with the author, and the like. According to Genette, epigraphs have the privilege of being closest to the text: he actually says they exist on the “edge” of a text. Epigraphs therefore indicate a border or a boundary to be crossed. In light of this, it seems telling that Gubaidulina’s choice of epigraph, a setting of the words “I thirst,” indicates desire. In the context of the Passion, these are the only egocentric words spoken by Jesus: they humanize him and express the very human needs that result from his suffering. Aside from the obvious literal interpretation, one could argue that Jesus, too, desires to cross a boundary from his human life to life eternal. The elements of suffering and desire present in these words no doubt resonated with Gubaidulina: transcendence and transfiguration are common themes in many of her works.

Gubaidulina notes that in Sieben Worte, the epigraphs come at the end of movements, thus they are not pro-spective but rather retrospective, forcing the listener to interpret the material that came before in terms of the epigraph. Genette says of the terminal epigraph, “It is the last word, even if the author pretends to leave that word to someone else” (149). According to Genette, epigraphs have four functions: 1) commenting on and/or justifying the title of the work; 2) commenting on the text; 3) suggesting the company one keeps (or wishes to keep); and 4) marking the period, style, or genre of the work. The first function, commenting on or justifying the title, is “almost a must in cases where the title itself consists of a borrowing,” says Genette (157). The quotation from Schütz makes sense in this case: it justifies Gubaidulina’s choice of a title, and positions her setting among efforts by other composers, which to some extent satisfies the third function as well. In this regard it initiates a dialogue with those works, asking the listener to consider her composition in the context of the others. The second function, commenting on the text, seems well suited for a terminal epigraph such as this: the genesis of the twisting semitonal figure of the first movement’s opening is illuminated by the Schütz quotation.

Another way to interpret the function of this quotation is in terms of the perception of time and temporality in Gubaidulina’s music. She speaks of art as manifesting a “continual present:” “the present is always elusive, suspended between a past that is no longer and a future that is not yet. From the perspective of art the present acquires a superior force of concentration on objects and concepts—it escapes from temporality” (Fisk 462). Her observations call to mind Jonathan Kramer’s theories of musical time, as well as more recent work by theorists like Michael Klein. To me, the opening of the first movement of Sieben Worte exemplifies what Kramer calls “non-linear” time, which is akin to Stockhausen’s concept of moment form: it entails, as Gubaidulina notes, a focus on the object, of a single moment in time. Clock time is suspended in this instance as we enter a state of contemplation. The suspension of clock time is reinforced by the lack of functional tonality, predictable rhythmic and metric figures, and the obsessive focus on the pitch A.

In contrast, the quotation from Schütz is very much goal-directed, tonal motion. It restores a sense of linear time in two ways. First, it has a clear tonal, rhythmic, and metrical structure. Taken altogether, the gesture is clearly cadential: it can be heard as a half cadence in E major (minor?). A half cadence serves a dual function: by virtue of its cadential function, it implies an ending of some sort. On the other hand, because the cadence is on the dominant, the gesture suggests a continuation. Thus Schütz’s figure moves us through time. The second way that Schütz’s quotation invokes a linear conception of time is by virtue of its antiquity. The work was composed in 1645, and thus connects us to a distant time and place: it represents an historical consciousness. That the quotation provided thematic material for much of Gubaidulina’s composition is suggestive of the past’s continuing presence and influence. To sum up: Sieben Worte uses quotation as part of a broader exploration of time and temporality. The juxtaposition of non-linear and linear time, the play of past and present, all call attention to the complex nature of the elusive present.