(I posted this on my clock app page too…)

In a previous video, I mentioned that I had a theory about where this “Bach created the rules of theory” idea came from. Allow me to introduce you to Allen McHose, who was a music theory professor at Eastman from the late 1920s until the late 1960s. He wrote a theory textbook called The contrapuntal harmonic technique of the 18th century, which was published in 1947.

The book examines the 371 Bach chorale harmonizations and presents some general observations about the nature of harmony in the 18th century based on this study. In the introduction, McHose writes: “The approach in the study of the material presented in this text involves emphasis upon the style of the music. This establishes a norm from which comparative studies with other periods may be readily achieved. Having as a basis a thorough knowledge of one technique of composition, one can accurately determine the outstanding characteristics of another style”

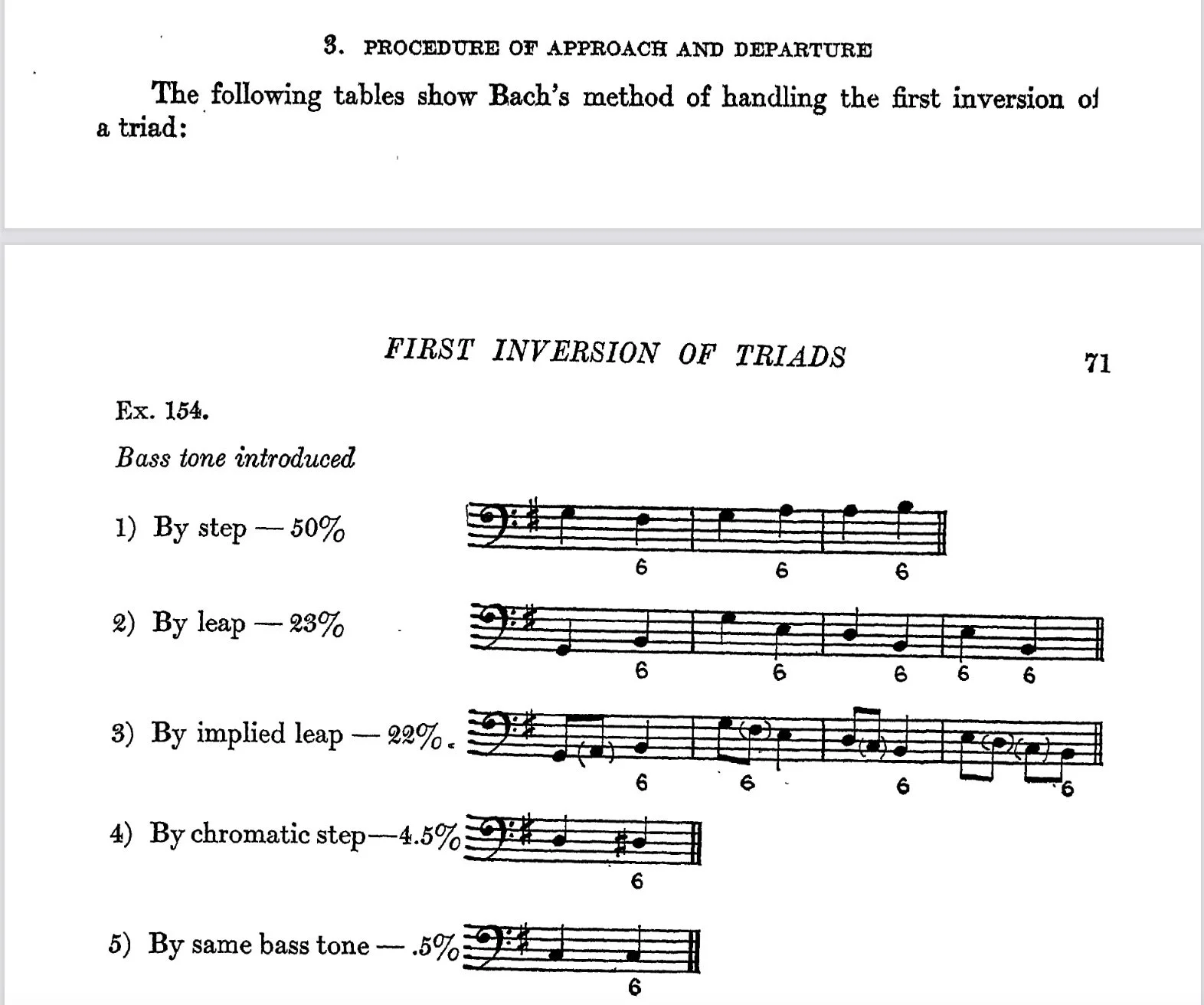

Here is a page from the book from the chapter on first-inversion chords: statistically speaking, Bach introduces the bass note of a first-inversion triad by step 50% of the time, by leap 23% of the time, and so on. McHose calculates his data to the half a percentage point, and uses these observations to create general “rules” for harmony and voice leading. For example, in a discussion of authentic cadences, he observes that “a rule formulated to drive the leading tone to the tonic when it is approached from below is questionable, in view of Bach’s treatment of the perfect authentic cadence.”

It’s worth noting that McHose was trained in chemical engineering—he was actually working on a master’s degree when he made music an integral part of his life again. I don’t doubt this scientific background influenced his statistical approach to Bach’s music.

There are definitely echoes of McHose’s book in Kostka-Payne’s Tonal Harmony textbook, which for a long time was the most widely used theory textbook in the US. This shouldn’t be too surprising, since Kostka also spent a bit of time teaching at Eastman in the late 60s and early 70s. The chord root approach, for instance, and even some of the language about voice leading is almost identical.

But both McHose and Howard Hanson, who was director of the Eastman school at the time and who wrote the forward to the textbook understood that this was not the theory, but rather a jumping-off point for developing other theories about music from different eras. Hanson writes: “The constant emphasis on the study of style reflects the author’s firm belief that a technique can be studied only in terms of the style of the period under discussion—that what is “wrong” for one period may be “right” for another. […] That the author should choose the style of Bach as a basis for this study seems entirely logical since the music of this master better than any other exemplifies the most perfect synthesis of harmonic and linear writing.” Such a claim is problematic in a few ways, but that’s a different story for a different day.

So I would point to McHose’s statistical study of the Bach chorale harmonizations as one important source of this “Bach invented the rules of music theory” cliche that tends to circulate. In my research, I’ve uncovered some more pretty interesting stuff and will share it soon!